Explore how English and other Western words are integrated into Korean and Japanese. This article examines phonetic adaptation, semantic shifts, and cultural factors that shape foreign vocabulary in each language.

1. Introduction: Western Words Enter the East

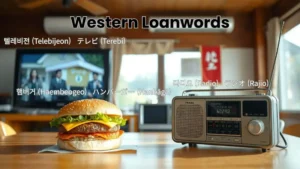

When Western technology, culture, and products began flowing into East Asia during the 19th and 20th centuries, both Korea and Japan faced the same linguistic challenge: how to name things that had no existing equivalent in their languages. From “coffee” to “train” to “democracy,” new concepts arrived quickly, and local speakers had to decide how to incorporate these words into their own linguistic systems.

Japanese and Korean both turned to loanwords, but the way each language absorbed and transformed them was far from identical. While Japanese often adapted foreign words phonetically, reshaping them to fit within its syllabic structure, Korean followed a different path, drawing selectively from Japanese imports while also adopting words directly from English and other Western languages in later decades.

This section introduces the broader historical context: how external influences entered Korea and Japan, how words were filtered through layers of translation and adaptation, and why the same “foreign” origin often resulted in very different vocabulary in the two languages.

2. The Historical Journey of Loanwords into Korean and Japanese

The story of loanwords in Korean and Japanese is both fascinating and complex. Despite their geographical proximity and shared use of Chinese characters historically, the two languages took remarkably different paths in adopting foreign words—particularly from English and other Western languages in modern times.

In Korea, loanwords started entering the language more aggressively in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, coinciding with rapid modernization and the introduction of Western technology, culture, and education. Interestingly, many of these words were adapted not only phonetically but also morphologically, blending seamlessly into Korean grammar. Words like 컴퓨터 (computer) or 인터넷 (internet) feel native because they follow Korean syllable structures and pronunciation rules, even though their origin is unmistakably foreign.

Japan, on the other hand, embraced foreign words slightly differently. Loanwords, known as 外来語 (gairaigo), became especially prominent after the Meiji period, when Japan opened up to the West. The Japanese approach often retains more of the original pronunciation, but still adjusts to Japanese syllabary constraints. This can be seen in words like コンピュータ (konpyūta) or インターネット (intānetto). Unlike Korean, where the adaptation often emphasizes ease of integration into everyday speech, Japanese loanwords sometimes preserve the foreign “feel,” making them sound distinctively international even to native speakers.

Beyond English, both languages also borrowed terms from other languages such as Dutch, Portuguese, and German during earlier periods of contact. Korea, for instance, absorbed a number of Japanese-transmitted Dutch terms during the late Joseon period, while Japan incorporated Portuguese words during the 16th and 17th centuries.

The divergence in adaptation strategies reflects more than just phonetic choices. It mirrors cultural attitudes towards foreign influence, the role of education, and societal openness to linguistic innovation. In short, loanwords became a mirror reflecting each society’s engagement with the outside world.

3. Phonetic and Semantic Adaptation of Loanwords in Korean and Japanese

When foreign words enter a language, they rarely retain their original sounds or meanings intact. In both Korean and Japanese, borrowed terms have undergone distinct processes of pronunciation adjustment and meaning refinement over time, reflecting each language’s unique phonetic structure and cultural context.

1. Modifying Pronunciation to Fit Native Sounds

Loanwords are frequently reshaped to match the phonological system of the borrowing language. In Korean, for example, English words are adjusted to comply with the syllable structure and consonant-vowel patterns of Hangul. “Computer” becomes 컴퓨터 (keom-pyu-teo), fitting neatly into Korean phonetics. Similarly, Japanese adapts foreign sounds to its mora-based rhythm. “Coffee” becomes コーヒー (kōhī), which reflects both the local phonotactics and accent patterns.

These adjustments are more than simple transliterations. They illustrate how each language integrates foreign sounds organically, ensuring the borrowed terms feel natural to native speakers while preserving recognizability.

2. Refining Meanings Over Time

Beyond pronunciation, loanwords often experience semantic narrowing, where the original breadth of meaning becomes more focused. For instance, the English word “service” has multiple senses, from customer service to military service. In Korean, 서비스 (seobiseu) is mostly associated with customer-oriented offerings, such as free items or perks in stores. In Japanese, サービス (sābisu) has a similar commercial nuance, but can also imply informal assistance or gestures in a broader social context.

Over generations, these subtle shifts accumulate, leading to meanings that are closely tied to local culture and usage patterns. Learners must understand not only the pronunciation adaptations but also how the meanings of borrowed words evolve in practice.

3. Parallel yet Distinct Paths

Although both Korean and Japanese borrowed extensively from the same foreign sources—particularly English in modern times—the way these words are phonetically integrated and semantically specialized is unique to each language. Korean emphasizes syllable-based adaptation within Hangul, while Japanese balances moraic rhythm with katakana representation. Similarly, the semantic trajectory of loanwords reflects societal norms, commercial practices, and everyday usage, producing distinct but parallel evolutionary paths.

4. How Korean and Japanese Adapt Foreign Words Differently

Korean and Japanese have both absorbed foreign words over the centuries, yet the ways each language adapts these words reveal striking differences. When a new term enters the lexicon, it is not simply copied; instead, it is reshaped to fit the native sound patterns and grammatical rules of the language. This process often leads to subtle shifts in meaning, usage, or nuance.

In Korean, foreign words—especially from English—tend to be simplified to match the syllable structure of Hangul. For instance, “computer” becomes 컴퓨터 (keom-pyu-teo), where consonant clusters are broken down and vowels are inserted to align with Korean phonotactics. Over time, some of these borrowed words acquire additional connotations or specialized usage, a phenomenon linguists call semantic narrowing. For example, the English word “service” in Korean often specifically refers to free additions or perks, which is narrower than its broad English meaning.

Japanese, in contrast, uses Katakana as the primary script for foreign loanwords, which allows the preservation of syllable sequences closer to the original pronunciation. Yet, pronunciation still undergoes adjustment to suit Japanese phonology. The word “computer” becomes コンピュータ (kon-pyu-ta), keeping the consonant-vowel structure that Japanese favors. Semantic shifts occur as well; words borrowed into Japanese can take on nuances that reflect social or cultural expectations. A term like “fashionable” might be rendered as オシャレ (oshare), which conveys not only style but also a certain sophistication or charm, a shade of meaning absent in the source word.

These adaptation patterns illustrate a key linguistic principle: foreign words are never entirely neutral when they enter a new language. They are filtered through native sounds, grammar, and cultural frameworks. In both Korean and Japanese, this reshaping has led to fascinating divergences between how a word is pronounced, its connotations, and the contexts in which it is used. The resulting vocabulary is both a reflection of external influence and a mirror of internal linguistic identity.

5. Modern Implications of Loanword Adaptation in Korean and Japanese

The way foreign words have been integrated into Korean and Japanese continues to shape modern communication, education, and media in each country. In contemporary society, these adapted words are not just linguistic artifacts—they actively influence daily life, marketing, and cultural perception.

In Korean, loanwords often appear in advertising, pop culture, and everyday conversation. A single English-derived word can carry a variety of connotations depending on context. For example, 서비스 (service) is commonly used in restaurants to indicate complimentary items, while 아웃소싱 (outsourcing) is reserved for corporate or professional contexts. These semantic nuances are a result of the way Korean adapts foreign terms to align with cultural expectations and practical usage, often narrowing or refining their original meanings.

In Japanese, Katakana words permeate almost every aspect of modern language. They appear in technology, fashion, food, and entertainment, sometimes taking on subtle shades of meaning that differ from the original source. For instance, スマート (smart) in Japanese commonly suggests sleekness or elegance, rather than intelligence alone, illustrating how semantic shifts reflect local cultural norms. Similarly, borrowed terms often interact with existing Japanese words, creating hybrid expressions that carry layers of meaning, such as パソコン (pasokon) for personal computer, a contraction of パーソナルコンピュータ, which also conveys familiarity and everyday utility.

These adaptation processes can sometimes cause confusion in cross-cultural communication. A word familiar in Korean might have a different nuance in Japanese, and vice versa. Understanding these subtle differences is crucial for translators, educators, and anyone navigating East Asian languages in professional or social contexts.

Overall, the continued evolution of loanwords highlights the dynamic relationship between language and culture. Both Korean and Japanese show how foreign terms are not merely imported—they are transformed, refined, and localized, creating vocabularies that are distinctly tailored to each society’s phonetics, semantics, and cultural values.

6. Conclusion – The Ongoing Impact of Loanwords in Korean and Japanese

Examining the adaptation of foreign words in Korean and Japanese underscores the fluidity of language and its responsiveness to cultural and societal needs. While both languages borrow extensively from English and other foreign sources, the methods and outcomes of these adaptations are distinct, reflecting each society’s phonetic, semantic, and cultural priorities.

In Korean, loanwords are carefully tailored to fit native sounds and syntactic structures. Their meanings often become context-dependent, allowing a single borrowed term to carry specialized interpretations across different social or professional domains. This selective adaptation has contributed to a modern lexicon that is dynamic yet familiar to Korean speakers, enabling effective communication while preserving linguistic harmony.

In Japanese, loanwords are seamlessly integrated into the existing writing system, frequently taking Katakana forms that coexist with native and Sino-Japanese vocabulary. Semantic shifts and localized nuances give these borrowed terms unique identities, often diverging significantly from their original meanings. This process illustrates how Japanese balances foreign influence with cultural coherence, creating expressions that resonate with both everyday life and professional discourse.