Explore how language transfer influences second language acquisition, including challenges, learner errors, and strategies for effective teaching.

1. Introduction

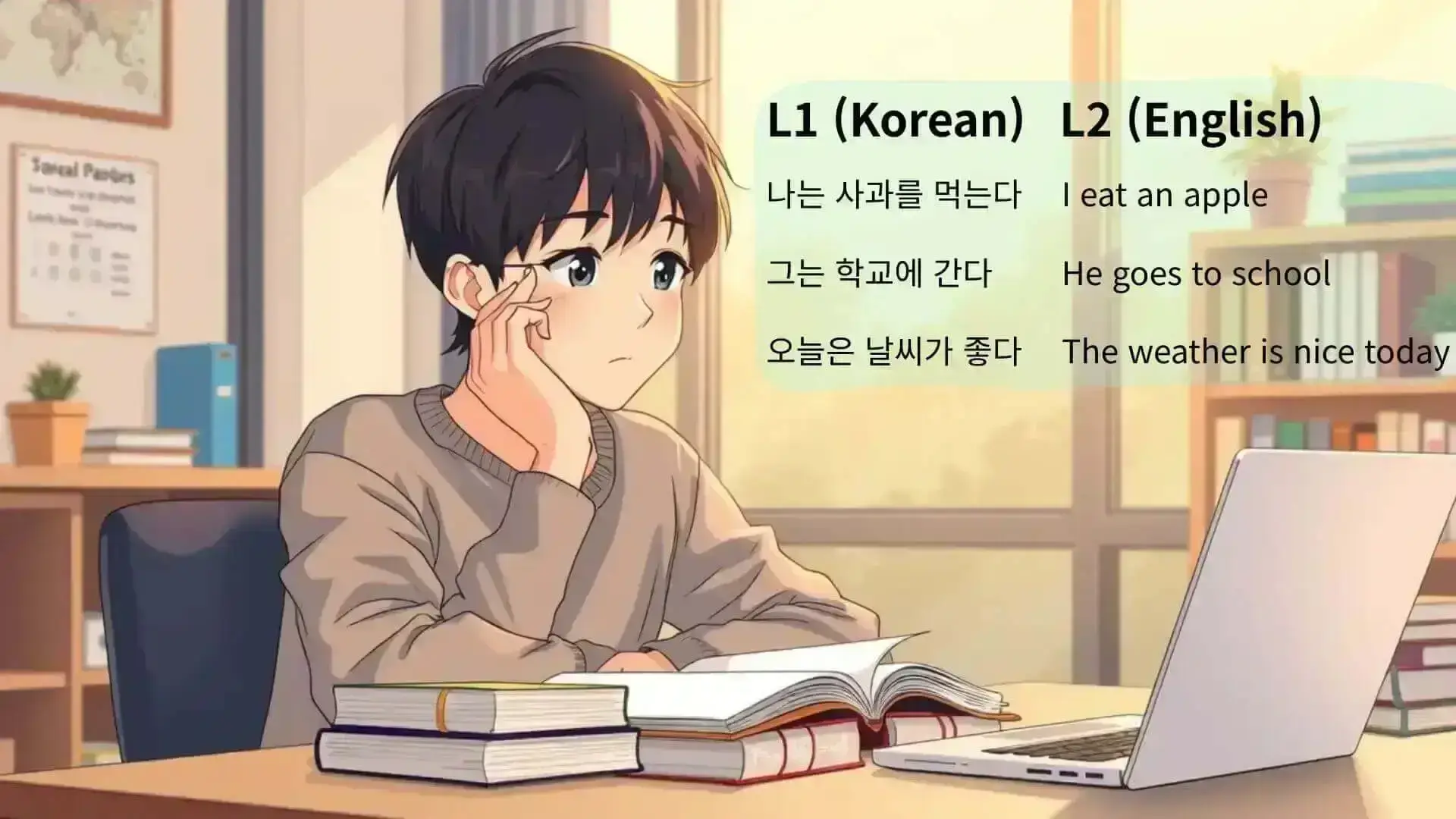

When learning a second language (L2), a learner’s first language (L1) often plays a pivotal role. The patterns, structures, and habits acquired in L1 influence how new linguistic forms are perceived, processed, and produced in the target language. This phenomenon, widely recognized in second language acquisition (SLA), is referred to as language transfer.

The concept of transfer is not new. Early research in the 20th century, particularly under the Contrastive Analysis Hypothesis (CAH), emphasized that similarities and differences between L1 and L2 could predict areas of learning difficulty. For instance, when L1 and L2 share similar grammatical structures, learners often acquire these aspects more easily, a phenomenon known as positive transfer. Conversely, when L1 and L2 differ significantly, interference may occur, leading to errors known as negative transfer.

Understanding transfer is essential because it provides insight into why learners struggle with certain features of the target language while easily acquiring others. Moreover, recognizing both the facilitating and interfering effects of L1 allows educators to design more effective teaching strategies. By acknowledging the dual role of transfer as both an obstacle and a resource, language instructors can better support learners in navigating the complexities of L2 acquisition.

2. Defining Language Transfer

Language transfer refers to the influence of a learner’s first language (L1) on the acquisition and use of a second language (L2). This influence can appear in grammar, vocabulary, pronunciation, and pragmatics. Understanding transfer helps explain why learners sometimes produce errors in L2 and why certain features may be easier to acquire than others.

Transfer can be categorized into three main types:

- Positive transfer (facilitation): Occurs when similarities between L1 and L2 make learning easier. For example, similar word order or shared vocabulary can accelerate acquisition.

- Negative transfer (interference): Happens when differences between L1 and L2 cause errors. For instance, learners may omit elements that exist in L2 but not in L1.

- Zero transfer: Arises when no equivalent structure exists in L1, requiring learners to acquire a completely new system. An example is the Korean honorific system, which has no direct equivalent in English.

Recognizing these distinctions is crucial for both educators and learners. Positive transfer can accelerate acquisition, while negative and zero transfer require targeted instructional strategies to prevent persistent errors. By systematically analyzing transfer, teachers can anticipate common difficulties and provide learners with clearer guidance in navigating the differences between L1 and L2.

3. Types of Transfer

Language transfer can occur in multiple ways, depending on whether the influence originates from a learner’s first language (L1) or emerges within the second language (L2) itself. These two main categories are interlingual transfer and intralingual transfer.

3.1 Interlingual Transfer

Interlingual transfer, also called cross-linguistic influence, occurs when features of L1 affect L2 acquisition. This includes grammar, vocabulary, phonology, and syntax. Interlingual transfer can involve:

- Absence of L2 category in L1 (Predlusive interference): When L1 lacks certain L2 features, learners may omit or misuse them. For example, Korean learners may omit English articles because Korean does not have an article system.

- Inappropriate application of L1 patterns (Intrusive interference): Learners may apply L1 structures in L2 contexts incorrectly. For instance, Korean learners might say “I apples eat” instead of “I eat apples,” reflecting SOV word order from Korean.

3.2 Intralingual Transfer

Intralingual transfer happens within the target language itself, often linked to the learner’s developmental stage. It involves overgeneralization or simplification of L2 rules. Common examples include:

- Overregularization of past tense: “I sleeped well” instead of “I slept well.”

- Misapplication of modal verbs: “She must sleeps” instead of “She must sleep.”

Both interlingual and intralingual transfer shed light on different sources of learner errors. Interlingual transfer highlights L1 influence, while intralingual transfer reflects natural developmental patterns in L2 learning. Understanding these distinctions is essential for effective teaching strategies and diagnostic assessments.

4. Transfer in Different Language Pairs

Language transfer manifests differently depending on the combination of L1 and L2. Comparing Korean and Japanese learners of English illustrates how structural similarities and differences influence learning outcomes.

4.1 Korean Learners of English

Korean learners often face challenges due to typological differences between Korean (SOV) and English (SVO). Common interlingual errors include:

- Article omission: “She read newspaper” instead of “She read a newspaper.”

- Plural marker misuse: “three cat” instead of “three cats.”

- Word order interference: “I homework do” instead of “I do homework,” reflecting the SOV structure of Korean.

4.2 Japanese Learners of English

Japanese learners also exhibit transfer effects, but patterns differ due to differences in L1 structure. Typical errors include:

- Verb tense and aspect errors: “She write letter yesterday” instead of “She wrote a letter yesterday,” due to differences in tense marking in Japanese.

- Politeness overgeneralization: Overuse of formal markers in contexts where simpler phrasing is natural in English.

- Articles: Fewer article-related errors than Korean learners, but mistakes like “I saw movie” instead of “I saw a movie” can still occur.

4.3 Comparing Korean and Japanese Learners

Both Korean and Japanese share an SOV word order, which generally reduces difficulty in adjusting to English sentence structure. However, key differences affect error patterns:

- Korean lacks articles entirely, leading to frequent omissions in English.

- Japanese has a topic marker system, which can partially align with English determiners, resulting in fewer article omissions but other syntactic challenges.

These examples highlight that even typologically similar languages can produce distinct transfer effects. Awareness of specific L1-L2 interactions is crucial for educators in anticipating learner difficulties and tailoring instruction accordingly.

5. Transfer and Language Difficulty

The concept of language transfer is closely linked to the difficulties learners experience when acquiring a second language (L2). One key factor is typological distance, which refers to how structurally similar or different a learner’s first language (L1) is to the target language (L2). Languages that share more features with L1 tend to be easier to acquire, while typologically distant languages often present greater challenges.

For example, Korean speakers learning Japanese generally encounter a shorter learning curve because both languages share similar word order (SOV), verb conjugation patterns, and other grammatical features. In contrast, Korean learners of English face greater difficulty due to differences in word order (SVO), the presence of articles, and plural marking, which do not exist in Korean.

Research supports this perspective. Odlin (1989) discusses how similarities and differences between L1 and L2 can influence learning outcomes, highlighting that transfer effects can either facilitate or hinder acquisition.

Additionally, Jarvis & Pavlenko (2008) introduce the notion of conceptual transfer, showing how cross-linguistic differences in categorization and construal can affect L2 learning. Their study emphasizes that structural, cognitive, and conceptual differences between languages play a crucial role in learner difficulties.

By understanding typological distance alongside transfer types, educators can anticipate common difficulties and design targeted instructional strategies. This approach allows teachers to support learners more effectively, turning potential obstacles into opportunities for accelerated and accurate L2 acquisition.

6. Transfer and Error Analysis

Language transfer and error analysis (EA) are closely related but distinct concepts in second language acquisition (SLA). Transfer focuses on the influence of a learner’s first language (L1) on the second language (L2), while error analysis examines the errors learners produce, regardless of their origin. Understanding both perspectives provides a more complete picture of learner difficulties.

The Contrastive Analysis Hypothesis (CAH) predicted that errors in L2 primarily stem from differences between L1 and L2. While CAH offered valuable insights, it often overemphasized interlingual errors and underestimated developmental errors arising naturally within L2 itself.

6.1 Interlingual vs. Intralingual Errors

Errors can be classified according to their source:

- Interlingual errors: Stem from L1 influence. For example, Korean learners may omit articles, producing sentences like “He has dog” instead of “He has a dog,” or “She read newspaper” instead of “She read a newspaper.”

- Intralingual errors: Result from overgeneralization or simplification of L2 rules. For instance, learners may say “She goed to school” instead of “She went to school,” or “They eated lunch” instead of “They ate lunch.”

Distinguishing between interlingual and intralingual errors allows educators to diagnose the underlying reasons for mistakes. Interlingual errors highlight areas where L1 and L2 differ structurally, while intralingual errors reflect natural developmental stages in L2 learning. Recognizing these distinctions helps teachers design targeted exercises, anticipate common difficulties, and provide corrective feedback that supports learner progress effectively.

7. Pedagogical Implications

Understanding language transfer has significant implications for teaching. By recognizing how L1 influences L2, educators can develop more effective strategies for instruction, error correction, and curriculum design.

7.1 Raising Learner Awareness

Teachers can help learners anticipate potential difficulties by highlighting contrasts between L1 and L2. Explicit awareness of these differences enables learners to monitor their own production and reduce errors.

7.2 Curriculum and Materials Design

Instructional materials should target likely interference patterns and areas prone to error. Designing exercises that focus on these problem zones accelerates learning and supports correct usage.

7.3 Error Treatment in the Classroom

Errors should be seen as evidence of learning rather than mere mistakes. Teachers can address underlying causes, providing corrective feedback and structured practice to support L2 development effectively.

Overall, integrating awareness of transfer into pedagogy allows instructors to proactively guide learners, turning potential obstacles into opportunities for accelerated and more accurate acquisition.

8. Case Study: Key Learner Errors

To illustrate the practical impact of language transfer, this section examines representative errors made by Korean and Japanese learners of English. The examples focus on both interlingual and intralingual sources, highlighting patterns that can inform teaching strategies.

8.1 Korean Learners of English

- Article omission (interlingual): Example: “He sent letter yesterday” instead of “He sent a letter yesterday.” This reflects the absence of articles in Korean. Teaching tip: Visual aids showing article usage in context can help learners internalize the rule.

- Plural marker omission (interlingual): Example: “five cat are playing” instead of “five cats are playing.” Korean nouns are not marked for plural in the same way. Teaching tip: Group exercises contrasting singular and plural forms improve accuracy.

- Overgeneralization of past tense rules (intralingual): Example: “She buyed a gift” instead of “She bought a gift.” Reflects developmental stage of applying regular past tense rules. Teaching tip: Focused practice of irregular verbs helps learners internalize exceptions.

8.2 Japanese Learners of English

- Tense/aspect misuse (interlingual): Example: “He go to school yesterday” instead of “He went to school yesterday.” Differences in tense marking in Japanese influence these errors. Teaching tip: Timeline exercises showing past, present, and future actions clarify correct tense usage.

- Politeness overgeneralization (interlingual): Example: “Could you please to help me?” in contexts where direct requests are natural in English. Teaching tip: Role-play with different social contexts demonstrates appropriate levels of politeness.

- Overregularization of regular verbs (intralingual): Example: “They eated lunch” instead of “They ate lunch.” Learners apply regular patterns to irregular verbs. Teaching tip: Mini-quizzes contrasting regular and irregular past forms reinforce correct forms.

8.3 Pedagogical Insights

By analyzing these cases, teachers can gain actionable insights:

- Interlingual errors highlight structural contrasts between L1 and L2 that benefit from explicit instruction.

- Intralingual errors reflect natural developmental patterns, requiring practice and reinforcement rather than direct correction only.

- Combining awareness of both error types allows instructors to design targeted exercises, anticipate common learner difficulties, and provide corrective feedback that addresses underlying causes.

9. Broader Perspectives

Language transfer extends beyond grammar and vocabulary, affecting pragmatics, culture, and pronunciation. Recognizing these broader effects helps teachers address challenges that are not purely structural.

9.1 Pragmatic Transfer

Pragmatic transfer occurs when learners apply L1 communicative strategies in L2 contexts. For example, Korean speakers may produce indirect refusals in English that sound overly vague to native speakers. Understanding such tendencies allows educators to teach culturally appropriate ways to express politeness or assertiveness in L2.

9.2 Cultural Transfer

Cultural transfer involves patterns of speech, politeness strategies, and social norms embedded in language. Korean and Japanese learners may transfer hierarchical or honorific systems into English, sometimes resulting in overuse of formal markers or awkward phrasing. Raising awareness of these differences can prevent misunderstandings and improve pragmatic competence.

9.3 Phonological Transfer

Transfer also affects pronunciation. Korean learners of English often struggle with sounds like /f/ and /p/, while Japanese learners may confuse /l/ and /r/. These difficulties stem from phonemes present or absent in L1, highlighting the need for targeted listening and pronunciation practice in language instruction.

By considering grammar, pragmatics, culture, and phonology, educators can adopt a holistic approach to language transfer. Addressing these broader perspectives ensures that learners are better prepared to communicate accurately and appropriately in real-world contexts.

10. Conclusion

Language transfer plays a dual role in second language acquisition, acting both as a facilitator and a potential source of errors. Positive transfer enables learners to leverage similarities between their first language (L1) and the second language (L2), easing the acquisition of familiar structures. Negative transfer, on the other hand, arises from differences between L1 and L2, producing errors that require targeted instruction.

Understanding transfer is essential for educators. By identifying interlingual and intralingual errors, anticipating difficulties based on typological distance, and addressing pragmatic and phonological challenges, teachers can design instruction that is both effective and learner-centered.

Approaching transfer as a resource rather than a problem allows instructors to support learners proactively. Structured practice, explicit instruction, and diagnostic feedback help mitigate negative transfer while promoting positive transfer, enhancing accuracy and learner confidence in navigating the complexities of L2.

Future research and pedagogical practice may continue to explore the interplay between transfer, error analysis, and interlanguage development, creating a comprehensive framework for supporting second language learners effectively.