Discover how identical Chinese characters developed distinct meanings in Korean and Japanese. This article explores the historical adoption, semantic evolution, and modern usage of Hanja and Kanji, revealing surprising differences in interpretation between the two languages.

1. Introduction

“Imagine looking at the same Chinese character, but a Korean and a Japanese speaker interpret it completely differently.”

This scenario highlights a fascinating phenomenon in East Asian languages. Chinese characters, which originated in China, were adopted by both Korea and Japan as integral components of their writing systems. Over time, however, these shared characters developed distinct meanings in each language—not just differences in pronunciation.

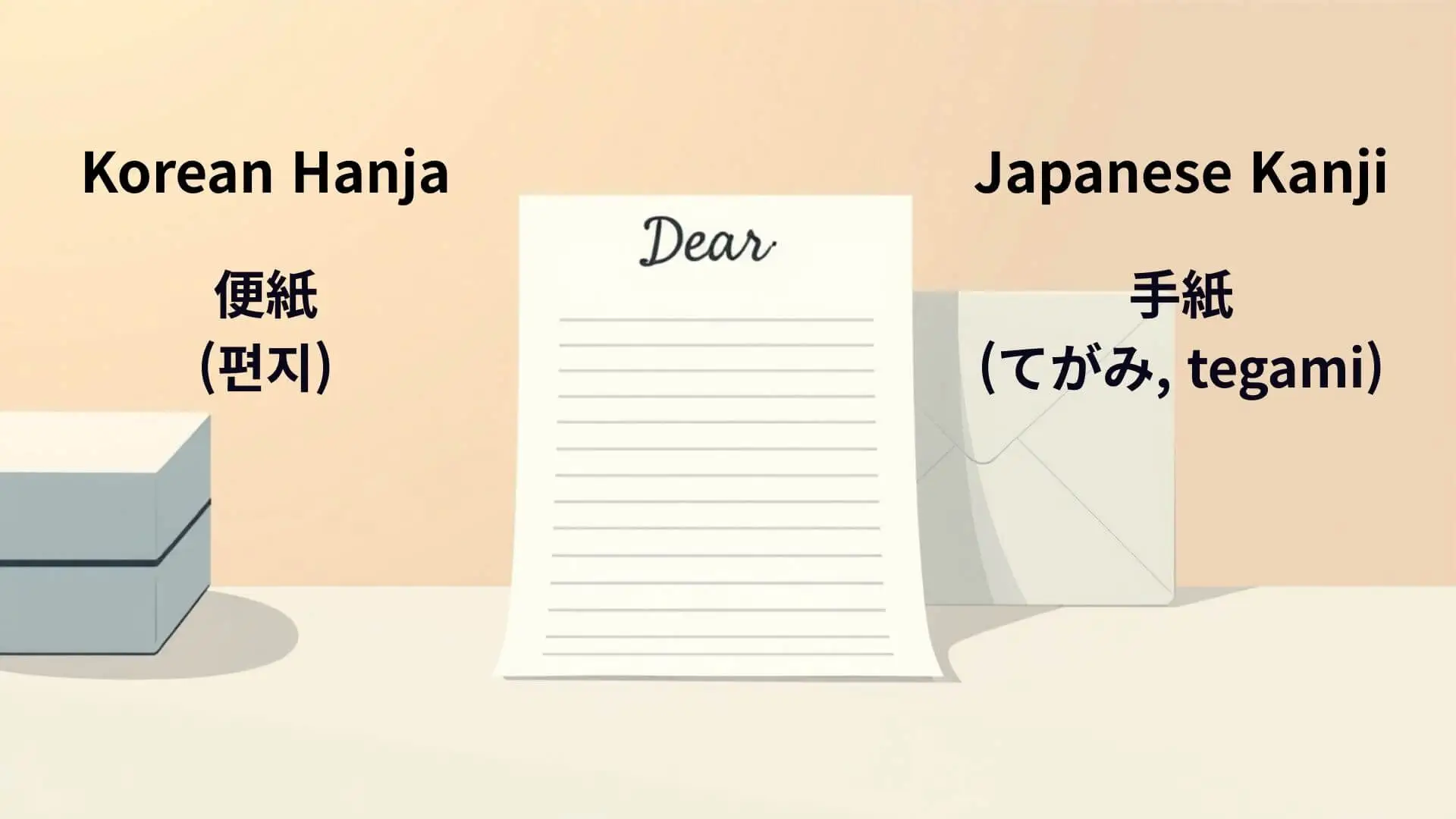

For instance, in Japanese, “手紙 (てがみ, tegami)” literally means “paper written by hand” and has come to signify a “letter.” In Korean, the word for “letter” is instead derived from 便紙 (편지) or 片紙 (편지), based on different combinations of Chinese characters. Similarly, “愛人” in Korean commonly refers to a romantic partner, whereas in Japanese, it can imply a lover in an extramarital or illicit relationship.

Such examples demonstrate that even identical Chinese characters can carry divergent meanings depending on cultural, historical, and linguistic contexts. This article explores these semantic divergences, revealing how the same writing system was adapted differently in Korea and Japan and how these adaptations continue to influence modern communication.

2. Historical Roots of Shared Characters

The story of Chinese characters in Korea and Japan begins over a thousand years ago. Both countries borrowed extensively from Classical Chinese, which was the scholarly and administrative language of East Asia. However, the paths of adoption and adaptation diverged, leading to differences not only in pronunciation but also in meaning.

Korea: Hanja and Its Limited Early Use

Chinese characters, or Hanja, entered Korea primarily during the Three Kingdoms period (57 BCE – 668 CE) through cultural exchange and the spread of Buddhism. For centuries, Hanja served as the principal writing system for official documents, literature, and scholarly communication.

With the invention of Hangul in the 15th century, literacy became more accessible to the general population. Hanja usage gradually became restricted to specific domains such as academic writing, legal texts, and personal names. This selective use of Hanja influenced how certain characters retained older or specialized meanings in Korean, while others evolved differently from their original Chinese context.

Japan: Kanji Integration into Everyday Life

In Japan, Kanji arrived around the 5th century CE, also through cultural exchange and Buddhist texts. Unlike Korea, Japan integrated Chinese characters more broadly into everyday language. Kanji was combined with two syllabaries—Hiragana and Katakana—allowing it to express both native Japanese words and borrowed Chinese vocabulary.

This integration encouraged semantic shifts: characters were not only pronounced differently but also adapted to Japanese concepts and social norms. Consequently, a single Chinese character could take on multiple readings and meanings depending on context, shaping a complex system that is still used in modern Japanese writing.

Divergent Historical Contexts

While both Korea and Japan shared the same pool of Chinese characters, differences in societal structure, literacy goals, and cultural integration led to unique semantic trajectories. Korea’s focus on administrative and scholarly use fostered a narrower, more formal set of meanings, whereas Japan’s wider adoption into daily life encouraged flexible interpretations and everyday usage.

These historical foundations set the stage for the surprising divergences in meaning that Korean and Japanese speakers encounter today, despite looking at the same characters.

3. Examples of Divergent Meanings

Even when Korean and Japanese share the same Chinese characters, the meanings assigned to them often differ dramatically. These divergences reveal how cultural context, historical usage, and linguistic adaptation can shape the way a character is understood in each language.

1. 手紙 (Shǒuzhǐ in Chinese)

Japanese: てがみ (tegami) – “letter,” referring to a message written and sent to someone. The character 手 (hand) and 紙 (paper) together literally mean “handwritten paper.”

Korean: 편지 (pyeonji) – also meaning “letter,” but traditionally derived from different Hanja like 便紙 or 片紙, showing a distinct lineage of usage. The point is that the exact same characters are not always the source of the word in Korean, which can lead to confusion if assumed otherwise.

2. 愛人 (Àirén in Chinese)

Japanese: あいじん (aijin) – “mistress” or “lover outside of marriage,” carrying a potentially scandalous connotation.

Korean: 애인 (aein) – “romantic partner” or “boyfriend/girlfriend,” a neutral or affectionate meaning.

3. 勉強 (Miánqiáng in Chinese)

Japanese: べんきょう (benkyō) – “to make an effort” or “study,” sometimes implying a forced or obligatory sense.

Korean: 공부 (gongbu) – “to study diligently,” with a neutral and purely educational nuance.

4. 大丈夫 (Dàzhàngfū in Chinese)

Japanese: だいじょうぶ (daijōbu) – “all right” or “okay,” used in everyday conversation.

Korean: 대장부 (daejangbu) – historically “great man” or “man of courage,” almost entirely different in meaning from modern Japanese usage.

Observations

These examples highlight that even visually identical characters can carry entirely different semantic loads in Korean and Japanese. The divergence is often a result of how each culture incorporated Chinese characters into local vocabulary, how meanings evolved over time, and the influence of other writing systems like Hangul and Kana.

4. Why Meanings Diverged

The differences in meaning between shared Chinese characters in Korean and Japanese are not random—they reflect deep-rooted historical, cultural, and linguistic factors. Understanding these reasons provides insight into how each language absorbed and adapted Chinese characters.

1. Historical Context and Timing of Adoption

Chinese characters arrived in Korea and Japan at different times and through different channels.

- Korea: Hanja was introduced during the Three Kingdoms period (57 BCE – 668 CE) and became a tool for official documentation, scholarly writing, and Buddhist texts. Its use was highly formalized and tied to elite intellectual circles.

- Japan: Kanji reached Japan around the 5th century CE, primarily via Chinese texts brought by scholars, missionaries, and immigrants. The Japanese often adopted Kanji into everyday vocabulary, allowing more flexible, colloquial usage.

The timing and context of adoption influenced which characters were preserved, how they were pronounced, and the meanings they developed.

2. Cultural and Social Influences

Cultural norms, social practices, and literary traditions shaped meaning differently in each country.

- Korean: After the invention of Hangul in the 15th century, literacy became more accessible, and everyday writing shifted to Hangul. Hanja remained primarily in formal, literary, or scholarly contexts. As a result, some character meanings narrowed or became specialized.

- Japanese: Japan integrated Kanji into daily life alongside Kana (Hiragana and Katakana). Characters were often repurposed, leading to nuanced or expanded meanings that could differ from their original Chinese sense.

3. Interaction with Native Writing Systems

The introduction of native scripts in both countries played a major role in semantic divergence.

- Korea: Hangul allowed phonetic writing of native Korean words, reducing reliance on Hanja for everyday language. Some Chinese characters were retained mainly for specific terms, leading to semantic narrowing.

- Japan: Kana scripts complemented Kanji rather than replacing them. This allowed Kanji to retain broad semantic ranges while integrating fully into spoken and written Japanese.

4. Evolution Over Time

Meanings naturally shifted as societies changed, new concepts emerged, and educational practices evolved.

- Characters that maintained formal or literary significance in Korea sometimes evolved into different, modernized meanings in Japanese.

- Conversely, some Kanji in Japan became specialized or nuanced over centuries, while their Korean counterparts were replaced by native words written in Hangul.

Summary

Semantic divergence is thus a product of historical adoption patterns, cultural context, interaction with native writing systems, and ongoing evolution. These factors together explain why identical Chinese characters can carry vastly different meanings in Korean and Japanese today.

5. Impact on Modern Communication

The semantic differences between shared Chinese characters in Korean and Japanese have practical implications for communication, translation, and cultural exchange. Even when a character looks identical, its meaning can vary depending on the linguistic and historical context, potentially leading to misunderstandings.

1. Misinterpretations in Daily Interaction

Shared characters can confuse learners or even native speakers encountering unfamiliar usage.

For example, the character 愛人 is interpreted as “lover” in modern Korean, implying a romantic partner, while in Japanese it usually refers to a mistress or extramarital partner. Misreading such characters can lead to unintended social awkwardness or offense.

Another case is 勉強: in Korean, it primarily means “to study diligently,” while in Japanese, it can carry a nuance of enforced effort or obligation.

These differences demonstrate that identical visual symbols do not guarantee identical meanings.

2. Translation Challenges

Translators and language learners must carefully consider context to avoid errors:

Literal translation of Kanji into Hanja or vice versa often fails to convey intended meaning.

Automated translation tools sometimes misinterpret characters, especially when used in idiomatic expressions or culturally specific contexts.

3. Implications for Education and Media

In language education, these divergences highlight the importance of teaching not just characters but also cultural and semantic context.

Japanese learners of Korean and vice versa benefit from comparative studies that clarify differences in meaning.

Media, literature, and international communication require awareness of these nuances to prevent confusion or miscommunication.

4. Opportunities for Cross-Cultural Insight

Despite potential pitfalls, these differences provide fascinating opportunities to explore cultural and linguistic evolution:

They reveal how societies adapt shared linguistic resources in unique ways.

Understanding these divergences enriches appreciation for historical influences, writing systems, and cognitive processing of language.

Summary

Semantic divergence among shared Chinese characters affects everyday interaction, translation, and education. Recognizing these differences enhances communication accuracy and provides deeper insight into the distinct cultural identities of Korea and Japan.

6. Conclusion: The Divergent Meanings of Shared Chinese Characters in Korean and Japanese

The study of shared Chinese characters in Korean and Japanese reveals that identical scripts do not necessarily convey identical meanings. Despite their common historical roots, centuries of linguistic evolution, cultural adaptation, and societal usage have created significant semantic divergences.

In Korea, the introduction of Hangul shifted Hanja to specialized contexts—such as academic terms, legal and official documents, and personal names—allowing the script to retain historical and cultural significance without dominating everyday writing or conversation.

In contrast, Kanji continues to play a central role in Japanese literacy, appearing widely in newspapers, literature, official communication, and daily conversation. Its integration into Japanese writing reflects an ongoing adaptation of Chinese characters to fit native phonetics, grammar, and cultural usage.