Explore how native European languages influence advanced learners of Korean. This article examines particle usage, pronunciation patterns, and prosody, offering insights for teachers and learners seeking accuracy and natural expression.

1. Introduction

Foreign speakers whose mother tongue is a European language often achieve impressive levels of Korean proficiency, yet native listeners frequently detect subtle, recurring differences. These differences are not random mistakes; they reflect systematic influences from learners’ first languages (L1). This post examines two broad patterns observed among European L1 speakers of Korean: (1) a tendency to omit or reduce certain Korean particles in spontaneous speech, and (2) persistent phonological and prosodic traits that reflect speakers’ L1 rhythm, vowel quality, and consonant articulation.

Understanding these patterns matters for both linguists and language teachers. From a theoretical perspective, they illustrate classic cases of L1 → L2 transfer and shed light on how morpho-syntactic, phonological, and suprasegmental systems interact during second language development. Practically, recognizing recurring tendencies helps instructors diagnose learner needs more quickly and design targeted activities that address the right features at the right stage.

Importantly, these L1-influenced patterns are not restricted to beginners. Even highly proficient learners can retain subtle traces of their native language due to fundamental articulatory habits, differences in phonological systems, and age-of-acquisition effects. Such persistence provides insight into second language acquisition processes and offers a framework for understanding both the challenges and opportunities faced by advanced learners.

In this article, I draw on observations of European speakers using Korean to highlight recurring L1 influences and their linguistic sources. Practical implications for teachers and learners are also discussed.

2. Theoretical Background: Transfer and Error Analysis

When learners of Korean consistently show patterns influenced by their native language, two frameworks are particularly useful for interpretation: language transfer and error analysis. These frameworks complement each other by explaining not only what learners do differently from native speakers, but also why certain patterns recur systematically.

Language Transfer

Language transfer occurs when structures, habits, or categories from a learner’s L1 affect their use of the L2. Transfer can be positive—when similarities between L1 and L2 facilitate learning—or negative, when L1 structures interfere with L2 production. For instance:

- Postpositional structures: Korean uses postpositions (e.g., -을/-를 for objects, -에 for location), similar to Japanese. A Japanese learner may transfer this familiarity positively. In contrast, speakers of English or German, whose languages primarily rely on prepositions rather than postpositions, may omit or misplace Korean particles in spontaneous speech.

- Word order and syntactic alignment: German has a relatively flexible word order, while English relies heavily on SVO. These habits can influence how learners construct Korean sentences, sometimes producing non-native word sequences even when grammar rules are technically known.

- Prosodic and rhythmic patterns: Stress-timed (English, German) versus syllable-timed (Romance languages) L1 rhythm affects Korean speech intonation, leading to subtle but perceptible L1 accents even at high proficiency.

Error Analysis

Error analysis goes a step further by systematically identifying the types and frequencies of errors. Instead of simply asking why errors occur, it categorizes them to distinguish between:

- L1-caused errors: predictable patterns due to transfer, such as particle omission or inappropriate use of tense/aspect markers.

- Developmental errors: arising naturally as part of second language acquisition stages, e.g., overgeneralizing verb conjugation rules.

- Interlanguage errors: unique constructions that are neither L1 nor L2-native but represent the learner’s evolving internal grammar system.

Together, transfer theory and error analysis provide a framework for understanding recurring patterns such as particle omission, unusual prosody, vowel substitution, or L1-influenced rhythm. These tools help linguists predict likely difficulties for specific learner groups and guide educators in designing targeted interventions.

In the following sections, real-world examples of European L1 speakers of Korean are analyzed through these lenses to illustrate how L1 influence manifests in advanced proficiency, highlighting both morpho-syntactic and phonological effects.

3. Case Examples: Particles, Pronunciation, and Prosody

This section examines recurring patterns observed among European L1 speakers of Korean, focusing on both morpho-syntactic and phonological traits. Real-life examples come from European-origin broadcasters in Korea, illustrating how first language (L1) influences persist even at advanced proficiency.

3.1 Particle Omission: Object Markers

A common pattern is the omission of Korean object markers -을/-를 in spontaneous speech. While subject markers 이/가 are rarely dropped, object markers often are. For instance, German-born broadcaster Daniel Lindemann says in a YouTube video:

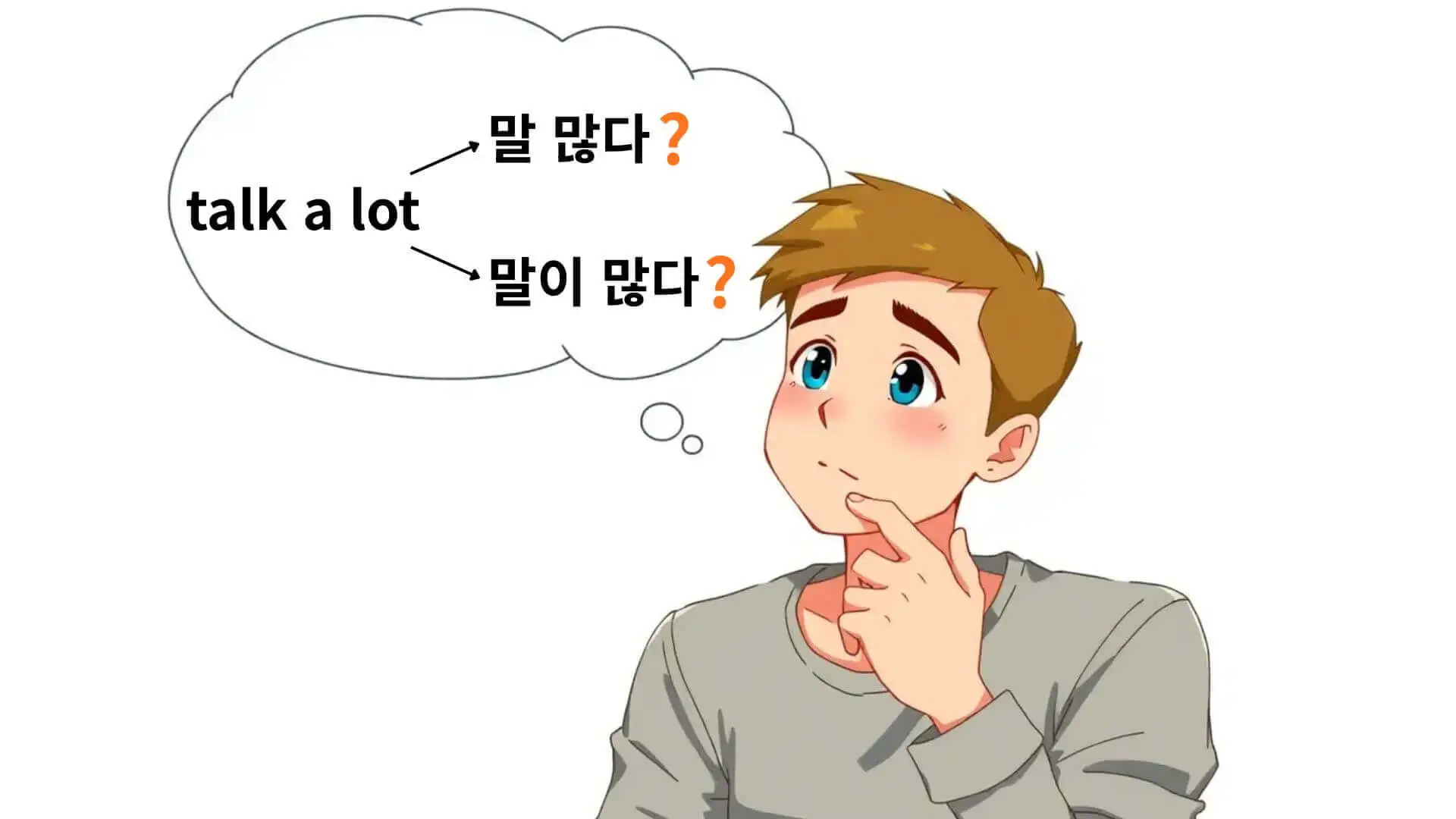

“그러면 우리가 일단 기본적으로 우리가 커뮤니케이션할 때, 일반인으로서 말 많이 하잖아요.”

Source: [지구촌 반상회_#193] 아니, 한국인들 자꾸 이러면 저희가 약간 힘드세요~^^

Although the sentence is understandable, a native Korean would typically say “말을 많이 하잖아요.” in that context. The omission aligns with English or German syntax, where objects do not require a postpositional particle. Learners transfer this habit from their L1, producing systematic omissions.

For comparison:

- 말이 많다 → talk a lot (English)

- 말이 많다 → (German)

Notice that in both English and German, no preposition is required for this type of expression. In contrast, when expressing location, time, or direction, prepositions are necessary (e.g., study at school, in der Schule studieren). This illustrates that the tendency to omit Korean object markers can be influenced by the L1 habit of omitting prepositions in similar constructions.

3.2 Segmental Transfer: Vowels and Consonants

European L1 speakers also exhibit segmental transfer in pronunciation. For example:

- French or Italian speakers often articulate Korean /ㅜ/ with strong lip rounding, similar to the French u.

- Italian speakers like Alberto Mondi and Cristina Confalonieri may lengthen or compress consonant closures, reflecting Italian articulatory habits.

- French-born broadcaster Ida Daussy also produces /ㅜ/ with a forward-protruded lip position typical of French, despite advanced Korean proficiency.

These variations are not random but reflect the influence of L1 phoneme inventories and articulatory patterns.

3.3 Suprasegmental Transfer: Rhythm and Intonation

Prosody and intonation provide another window into L1 influence. Romance-language speakers (French, Italian) often retain syllable-timed or mora-influenced rhythms, whereas Germanic-language speakers (German, English) exhibit stress-timed patterns. For instance:

- Ida Daussy, Alberto Mondi, and Cristina Confalonieri show L1-driven melodic contours in Korean speech.

- Daniel Lindemann (German) and Tyler Rasch (American) produce Korean with minimal L1 rhythmic influence.

These suprasegmental features—stress, syllable timing, and intonation—are robust in L1 and often persist into advanced L2, giving each speaker a subtly distinct accent pattern.

3.4 Likely Sources

- Particle omission: Transfer from European L1 syntax, where objects do not require postpositional markers.

- Phonetic variation: L1 vowel and consonant articulatory habits carried into Korean.

- Prosody and rhythm: Retention of L1 suprasegmental patterns, affecting stress, length, and melodic contour.

Overall, these patterns highlight that even highly proficient learners carry subtle L1 traces in morpho-syntax, phonetics, and prosody. Recognizing these influences is valuable for teachers and learners aiming for accurate and natural Korean.

4. Conclusion & Implications

Observations of advanced European L1 speakers of Korean—broadcast professionals such as Daniel Lindemann, Alberto Mondi, Cristina Confalonieri, and Ida Daussy—demonstrate that subtle traces of the native language persist even at high proficiency. These include omission of object markers, suprasegmental patterns such as vowel articulation and rhythm, and occasional phonetic variations.

Such L1 influences are not confined to beginners and do not necessarily hinder communication. In fact, a slightly “French-sounding” or “Italian-sounding” Korean can contribute to the speaker’s unique style, adding personality to their language use. Achieving 100% native-like Korean is not a necessary goal for effective communication.

At the same time, learners who aim for accurate and fluent Korean should recognize which aspects of L1 influence may interfere with comprehension or clarity. For instance, systematic omission of object markers or misplacement of particles can cause misunderstandings in formal or precise contexts. By identifying these areas, learners can focus on targeted practice to mitigate negative transfer without erasing the unique features of their speech.

For teachers and learners, awareness of L1 influence remains valuable. Explicit instruction, targeted pronunciation drills, grammar reinforcement, and reflective practice can help address potential obstacles, while embracing each learner’s unique style. By balancing linguistic accuracy with personal expression, learners can communicate confidently and authentically in Korean.